Reflections on the 2012 Presidential election

I haven’t talked about the 2012 presidential election in France (April 22/May 6) in much detail yet, largely because I prefer to analyse elections after the fact, because any analysis prior to any votes being cast is going to be based on a successions of polls, hearsay, personal opinions, and the usual political shenanigans and platitudes. There is also the fact that I personally can’t bring myself to care all that much about the campaign itself, though I anxiously await the results of the first round to develop some solid analyses and draw up some detailed maps of the results which will tell us, better than anything else, what exactly happened.

That being said, having been called upon by a good friend of mine who has dedicated himself to tracking (in French, naturally) the polls and patterns of this campaign to offer my analysis and point of view on a few matters of relevance to this campaign and the patterns which have emerged in the polls thus far. I felt it reasonable to put together a post with a few personal reflections and observations of the campaign (and the polls) thus far.

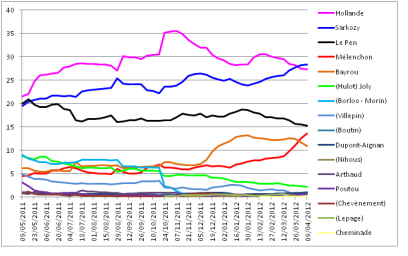

Voting intentions for the first round of the 2012 French presidential election (source: sondages2012)

My friend’s blog has developed an aggregate tracker of all polls published, which he can explain far better than I can. I have copied the graphical representation of this tracker since May 2011 on the right of the screen. The main trends since December 2011, which is when the campaign entered the “serious” part, have been as follows:

On the left, François Hollande (PS) has seen his poll ratings drop by a not inconsequential amount though not for that matter at an alarming pace. He had a brief bump in early February, following a very successful campaign rally at Le Bourget. The indicator pegs him at 27.3%.

On the right, Nicolas Sarkozy (UMP) saw his poll ratings grow at a steady and fairly rapid pace between late January and this week. He started gaining at a steady pace following the official announcement of his candidacy on February 15, and maintained his dynamique following a successful rally at Villepinte and the tragic shootings in Toulouse. Symbolically, Sarkozy has now surpassed Hollande in most polls for the first round. The indicator pegs him at 28.4%.

On the far-right, Marine Le Pen (FN) has seen her support drop about at the same pace as Nicolas Sarkozy increased his support. She is a long way from her headline-making peaks of the summer of 2011, when was roughly tied with Sarkozy. She is pegged by the indicator at 15.3%, which would be a strong showing for the FN but certainly an underwhelming performance for her considering her string of successes in 2011.

On the left, Jean-Luc Mélenchon (FG) has been the top mover-n’-shaker of the first round thus far. Now pegged at 13.5% by the indicator and polling as high as 15% in some polls, Mélenchon began a phenomenally rapid surge in early March, a surge which has yet to peter out though it is stabilizing at a ceiling of 13-15% for him. Explanations for this surge abound, and the answers are not as simple as the graph may indicate. Mélenchon’s dramatic emergence in this race, moving up from the second tier to the first tier and rivaling Marine Le Pen for third place has been the most important event of a rather uneventful, uninspiring and stale campaign thus far.

In the centre, François Bayrou (MoDem), after a successful rapid emergence in the first tier in December following his official announcement and the launch of his trademark industrial nationalism shtick (produire français) has failed to take his early dynamique any further despite a lot of potential openings for him since then. After stabilizing at a fairly decent 12-14%, he has since shed support at a fairly alarming pace, the indicator now pegging him at only 10.9%.

In the second tier, Eva Joly (EELV) has continued her slow descent into the abyss with an unabated and general decline in all polls from a strong 4-6% base in December to a stable 1.5-3% range today, the indicator placing her at 2.2%. None of the other four candidates (the DLR’s Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, the far-left’s Nathalie Arthaud and Philippe Poutou and the LaRouchite Jacques Cheminade) have been capable of gaining relevance – or even support consistently above 1% – since the serious things began. Their last chance will be the two-week long official campaign, where official television ‘spots’ by each candidate are run.

Based on these general trends, what are the main things we can take away from this and what are the explanations for these events?

1. Why the Mélenchon surge?

Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s surge, as aforementioned, is probably the most dramatic event of what has been a fairly boring and stale campaign. With support somewhere between 12 and 15%, Mélenchon could potentially place third.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a former Socialist cabinet minister and traditionally one of the top figures of the party’s left-wing, left the party following the chaotic Reims Congress (2008) to create the Left Party (PG) which claims to emulate the German Linke. Although the PG as an individual political party has an extremely limited base, it has the sizable benefit of having as its leader a dynamic, charismatic and assertive man who has proven capable of reinvigorating the left of the PS. In 2009, the PG allied with the Communist Party (PCF) – whose infrastructure, grassroots and traditional core electorate is much larger than that of the PG but which is totally devoid an inspiring, charismatic dynamic leader – to form the Left Front (FG) which achieved some success in both the 2009 European and 2010 regional elections.

The FG serves the interests of both partners. For the PCF’s leadership, an alliance with Mélenchon is a golden opportunity for them to regain political relevance and touch a wider base. In the 2007 presidential election, the PCF’s candidate, Marie-George Buffet – one of those boring party apparatchiks with which the PCF abounds – won a disastrous 1.9%, placing the party’s very survival into question. The FG, from the PCF Politburo’s point of view, is a terrific lifeline for them and allows them to reach out to voters who would not have considered voting for a party apparatchik like the party’s current boss, Pierre Laurent. For the PG, the FG is the tool with which Mélenchon can put his hands on a rather well-oiled political machine to further his political ambitions (the leadership of the “left of the left”).

Mélenchon was always going to perform much better than Marie-George Buffet (1.9%) in 2007, which is one of the main reasons why the bulk of the PCF’s base embraced him. However, beginning in January, he started creeping up from behind – without many observers taking note of it – largely because it was not a very dramatic boost, only slowly moving up from 6% to 8-9%. In early March, his surge began. The first signs of the surge actually happened prior to his massive rally at La Bastille in Paris, which is often cited as the moment at which his candidacy really took off.

What can explain this surge?

Firstly, there is his personality. He is charismatic, dynamic and extremely assertive. Besides his tendency to go on slightly amusing rants against journalists he has a grudge against, his demeanor and style – forcefully and passionately defending his political positions – seems to have convinced many left-wing voters who have been disappointed by Hollande, known for his more moderate tone. Though Hollande’s image as being “soft” is not entirely correct, it is not entirely false either. During the PS primary, Hollande’s main weakness was on his left, where he was open to criticism for his ‘softness’ and ‘weakness’. For a lot of left-wing voters who are very motivated by the urge to defeat Sarkozy and to dramatically change courses, Mélenchon can appear as a far more assertive and dynamic candidate than the “soft” Hollande whose campaign has been hesitant and fairly quiet since his successful outing at the Bourget.

Mélenchon has seen his ‘image’ improve considerably, though it is up for debate whether this is the result of the surge or if it is indeed a cause of the surge. In the past, his image as an angry, bitter man known for his tirades and bad temper against journalists gave him a fairly negative or at least polarizing image in the wider public opinion. However, voters seem to have rediscovered his charisma and dynamism, and in turn have judged him more favourably.

Mélenchon, to conclude on this point, has all the qualities needed for a successful candidate: charisma, a strong talent for the oratory, dynamic and appearing as a fairly honest person who believes in what he preaches, and who can convey his message forcefully and successfully. Hollande’s charisma is not horrible, but he certainly doesn’t have Mélenchon’s appearance as a skilled orator.

Secondly, there is the rhetoric. Mélenchon has successfully claimed the mantle of the anti-system/anti-establishment, somewhat ‘revolutionary’ candidate on the left of the spectrum.

There is a certain appetite and indeed some room in France, especially on the left and especially in times of economic crisis, for a candidate who takes a very anti-system message on issues such as the banks, high earners, tax evaders, austerity measures, social policies and defending the welfare state. Foreign observers are quick to note with some amusement how French voters always stand out in western Europe for their pronounced skepticism towards capitalism and globalization, and their penchant for economic populism and watered-down protectionism. It is hard to quantify (and I love quantifying stuff), but it is not unreasonable to claim that Mélenchon has taken on a stature as a forceful anti-system advocate for economically populist propositions (measures such as increasing the minimum wage to €1700, a ‘100% tax bracket’ on revenues above €360,000, a cap on maximum salaries) which tend to be popular in times of economic crisis.

Related to this above point, Mélenchon has likely become one of those candidates who is attractive to protest voters – those who “vote with their middle finger”. His whole rhetoric, standing outside the system and his tirades against big business and corporations, makes him a natural fit for these anti-system protest voters who in the past have flirted with the Le Pens but also, in 2007, with François Bayrou with his image as the “respectable” but still outsider, anti-system candidate.

In an Ipsos poll, 31% of his voters cited a “desire to reflect my discontent” as one of three main vote motivators – which is quite a bit above the national average (23%), but also far below the average for Marine’s voters (46%). He is not entirely a protest candidate. 22% of French voters cited “rejection of other candidates” as a vote motivator, but only 6% of Mélenchon’s voters cited this as a voting motivator (against 23% for Le Pen). For 78% of Mélenchon’s voters, his ideas or proposals were one of the top three voting motivators – the highest of any candidate besides Eva Joly. At this point, Marine Le Pen remains much more of a protest candidate than Mélenchon, but Mélenchon certainly has a base of support with these heterogeneous protest voters.

2. Where is Mélenchon’s surge coming from?

According to Ipsos, whose polling saw Mélenchon jump from 9.5% on March 3 to 13% on March 24, the vast majority of his gains come from voters who have switched their allegiance from another candidate. Ipsos estimates that Mélenchon gained 2% (out of 3.5%) from François Hollande, 0.5% from François Bayrou, 0.5% from Marine Le Pen and 0.5% from ‘other candidates’.

It seems quite reasonable that part of Mélenchon’s surge in the past few weeks came from voters who had previously supported Hollande. My theory on this matter is that Mélenchon gained the support of a fraction of the left-wing electorate which is very much anti-Sarkozyst and lying on the left of the PS. These voters may have supported Arnaud Montebourg in the PS-PRG’s open primary in 2011, but opted to support Hollande following his victory for reasons including party unity, ability to defeat Sarkozy and perhaps convinced by some of his left-wing planks (the 75% tax bracket).

However, these voters were likely frustrated by Hollande’s “soft” image following the Bourget, his inaudible campaign and in general his more centrist and moderate image which might have prompted some to support Montebourg or Martine Aubry back in the primary. For these voters, either from the left of the PS or on the fence between the PS and the “left of the left”, Mélenchon likely proved an attractive candidate who talks about the left-wing themes they want to hear and takes a forceful posture against Sarkozy. The media narrative about the inevitability of a Hollande-Sarkozy runoff, and how Hollande is the favourite dog in that race likely reduces the risk, for these voters, of voting for a candidate other than the top two. There is still a tendency on the left for the vote utile (‘useful vote’, aka voting for one of the top two contenders, not the also-rans) since the 2002 disaster, for it is not as prominent today with the narrative and appearance of Hollande’s inevitability. It is thus less risky for these voters, not too impassioned by Hollande but very determined to defeat Sarkozy, to vote for a candidate (Mélenchon) closer to their own views (which are likely to the left of Hollande) while still voting for Hollande without many second thoughts in the runoff.

Indeed, polls shows that about 85% of Mélenchon’s voters will vote for Hollande over Sarkozy in the runoff, with about one in ten of his voters likely to abstain and only a tiny fraction which will vote for Sarkozy. From this quantitative point of view, Mélenchon’s surge is not really a problem for Hollande (as long as it stabilizes at where it is now, 13-15%). However, from a qualitative point of view, one could argue that Mélenchon’s surge forces Hollande to tack left in the first round and perhaps in the runoff, in the process running the risk of losing more centrist voters who might edge towards Bayrou.

It is slightly more surprising to see Ipsos estimate that Mélenchon gained 0.5% from both Bayrou and Marine Le Pen. From a purely ideological point of view, Bayrou and Mélenchon do not have much in common – if anything at all. Marine Le Pen and Mélenchon are sworn enemies and polar opposites, especially after Mélenchon savaged her in a televised debate. However, ideology isn’t everything in the wonderful world of politics. We will come back to the issue of Marine vs. Mélenchon in more details later.

As for Bayrou’s voters switching to Mélenchon, it must first be said that this is only a small fraction and you could very well sketch it up to margin of error problems in the polls. If we are, however, to assume that some Bayrou supporters have switched to Mélenchon, what could be the cause? The most likely option is that Bayrou, in his December surge, picked up some of the voters who had backed him in 2007 not because of centrist-UDF traditions but rather because of Bayrou’s 2007 image as the “respectable” anti-establishment candidate. His whole “industrial nationalism” shtick (produire français/made in France), which is certainly very distant from the traditional internationalism of the UDF, might have been a factor in attracting some non-centrist ‘protest-type’ voters to Bayrou in December. When his campaign started to founder, however, he might have lost these fickle voters to Mélenchon who, while not hammering the industrial nationalism stuff, does in some regards come close to the contemporary political style of Bayrou or the 2007 image of Bayrou as the “anti-establishment candidate of the establishment”.

According to an Ifop study on the dynamique Mélenchon, Mélenchon attracts the support of 11% of Bayrou’s 2007 voters.

3. Marine Le Pen vs. Jean-Luc Mélenchon

It might be tempting and indeed obvious to connect Mélenchon’s surge with Marine Le Pen’s steady erosion of support (see the graph above). This theory brings us, incidentally, to the media’s favourite theory (and my pet peeve): that the FN’s rise to prominence in the 1980s was fairly directly correlated with the PCF’s decline. Certainly if you only look at graphs, the FN grew at the same time as the PCF declined. Hence, the story goes, Mélenchon might be attracting some old left-wing/Communist voters who had taken to voting for the Le Pens in recent years.

One cannot really dispute the idea that the FN attracted traditionally left-wing voters, usually lower middle-class or working-class, who were disappointed by the economic crises and corruption scandals of the Mitterrand years and attracted by the working-class, anti-immigration populism of Jean-Marie Le Pen and the FN. In past posts, I have talked at some length about the idea of gaucho-lepénisme which denotes a certain category of traditionally left-wing voters who vote for the FN in the first round but tend to vote for the left in the runoff. The 1990s, especially the 1995 presidential election, was perhaps the peak of gaucho-lepénisme, which subsequently declined a bit in 2002 but might have had a little renaissance of sorts in 2010-2011.

Let us be careful, however, about equating gaucho-lepénisme with some concept of a “communists for Le Pen” phenomenon. The media loves to claim that there exists a strong correlation between a Communist tradition and a strong FN base, while Communist sympathizers categorically deny any such correlation (often using the 1984 European elections as proof!). Neither side is entirely correct, because the issue can’t be black and white.

There are certainly grounds for PCF voters to switch to the FN: two protest parties, both attracting support from “unhappy” protest/anti-system voters, both speaking out against the big corporations and those who prey on the working poor. People vote the way they do for all kinds of reasons, and switch partisan allegiances in a manner which may appear crazy or contradictory. Thus, there is certainly a small minority of PCF voters who flirt with the FN on occasion. In 2002, 5% of Robert Hue’s 1995 voters voted for Jean-Marie Le Pen as did 7% of PCF sympathizers. In 2007, again, 7% of PCF sympathizers voted for Jean-Marie Le Pen. In 2010, only 1% of PCF-PG sympathizers voted for the FN though 6% of those who had voted for the FG in the 2009 European elections voted FN.

However, the FN’s gains in working-class areas since the late 1980s have been most important in right-wing working-class areas (they certainly exist) or left-wing working-class areas where the PS has tended to be the dominant party. Using a sample of 122 working-class municipalities with a significant population, there was, in 1995, a strong negative correlation of -0.56 between Hue and Le Pen, which was carried on to 2002 (-0.48) and 2010 to a lesser extent (-0.32). There was, in addition, a strongish negative correlation of -0.36 between the FN’s 2010 performance and Robert Hue’s 1995 performance. This is, of course, only a limited sample, but in these core working-class areas (the sample includes PCF, PS and right-wing dominated locales), the FN clearly performed much better in traditionally right-wing working class areas (Cluses-Scionzier, Oyonnax, Moselle’s mining basin, Mazamet or the Yssingelais for example) while its performances in historically Communist working-class areas was rarely very strong and much more often average, mediocre or even weak.

In the Nord-Pas-de-Calais, for example, the FN’s “new” working-class bases have historically been municipalities where the PS, not the PCF, dominated politics. Hénin-Beaumont, was just as left-wing as other surrounding mining basin communities, but the PCF has not been particularly strong there since the 1980s. Lens, Halluin, Roubaix or Tourcoing are other examples of PS-dominated working-class or working poor communities where the FN is strong. In contrast, the Communist strongholds of the mining basin in the same region (Divion, Auchel, Carvin, Avion, Denain, Saint-Amand-les-Eaux, Somain, Marchiennes) have not really distinguished themselves by particularly strong FN performances – even in the Marine-mania of 2010. The same results can be observed in Meurthe-et-Moselle and Moselle, where the PCF’s strongholds are weak points for the FN while working-class areas of Socialist or right-wing tradition tend to distinguish themselves by strong FN performances.

The traditionally Communist regions where the FN has tended to be strong tend to be inner suburban “red belt” municipalities (notably in Paris’ red belt but also the Rhône or Isère), where the presence of large immigrant communities might lead some old Communist supporters to switch allegiances to the FN. In addition, a lot of these inner suburban ‘red belt’ communities are no longer working-class areas but rather lower middle-class areas with large population of low-level employees, some public servants, other working poor, unemployed workers and so forth. The PCF’s lingering support in these inner suburbs as compared to “mining basin” urban areas (in the Nord or Lorraine) might be more the result of family tradition, local party infrastructure and Communist machinery than any remaining attachment to the parti du prolétariat.

Communist voters who abandon the party are more likely to switch their allegiances to the PS, or, between the 1990s and 2010, the far-left. Indeed, between about 1995 and 2007, the far-left – both Arlette Laguiller’s LO and later Olivier Besancenot’s LCR – was an attractive left-wing protest option for some working-class voters. In 2002, the far-left combined won 16% of the vote amongst ouvriers against only 3% for Robert Hue. In 2007, the far-left combined won 12% of their vote against only 2% for Marie-George Buffet. In 2002, 19% of those who had voted for Robert Hue in 1995 voted for either Arlette or Besancenot, while 11% voted for Lionel Jospin and only 5% for Jean-Marie Le Pen.

All this spiel can usefully point out that the correlation between PCF decline and FN gains is not as perfect as the old myth would like to make you think. But what about the links between FN decline and “left of the left” gains? The quantitative data on this is sparse, but very few people who vote FN tend to go back to vote for the PCF or the “left of the left”. In 2007, only 3% of Le Pen’s 2002 voters voted for one of the three far-left candidates and next to none of his 2002 voters voted Buffet. Same story in 1995, 2002 or 2010. If a Le Pen voter was to switch to the left, it would be to the far-left.

It is hard to see that much of Mélenchon’s gains came from voters who had once flirted with the possibility of voting for Marine. There is certainly some overlap, but I subscribe to the view that Mélenchon’s gains and Marine’s recent decline are not really correlated in any significant manner. Marine Le Pen’s decline is much more closely linked to Nicolas Sarkozy’s gains.

Ifop’s aforementioned study, to which we will come back to in more detail, showed that 3% of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s 2007 voters are opting for Mélenchon, which is very negligible. If you could ask Le Pen’s 2002 voters, I doubt the percentage would be significantly higher – considering that in 2007, Le Pen’s electorate had kept a lot of the working-class votes but shed a lot of the more middle-class or white collar votes of 2002.

It seems as if Mélenchon’s gains come on the backs of those voters who had abandoned the PCF in favour of either Arlette or Besancenot between 1995 and 2007. Given that in the absence of either of those two emblematic leaders of the far-left, their parties have been reduced to their “real” base (0.5-1%), Mélenchon has likely garnered the support of voters who voted for the far-left in the past two or three presidential contests.

Ifop’s study showed that Mélenchon stood at 63% support amongst those who had voted for Besancenot in 2007 – up 25 points from their first study on the Mélenchon vote. This is probably a small sample size, but it is not crazy to assume that Mélenchon’s surge came, in large part, from people who had voted for Besancenot in 2007 but who had put their votes “on the market” this year. It is not unreasonable, in this case, to assume that a small but significant share of the electorate shifted their sympathies from Arlette/Besancenot in 2007, Marine in 2011-2012 and abandoned Marine in favour of Mélenchon – perhaps as Marine Le Pen’s campaign was “back to basics” in terms of rhetoric (the old rhetoric on Islam, immigration, security; rather than her new working-class populism).

4. Who is voting Mélenchon?

Is Mélenchon ‘catching’ a working-class electorate, recreating the proletarian electorate of the PCF in the 1970s-1980s? Or is he instead appealing more to solidly left-wing public employees? The Ifop’s study on the Mélenchon phenomenon, very interesting and quite detailed, gives us a few answers.

In basic terms, Mélenchon’s electorate is more masculine than feminine and is heterogeneous in its age, appealing both to young voters (18-24) and older voters (50-64). He seems to have scored the most points with the youngest voters, with his support in Ifop’s March 13-27 pegged at 16% with those 18-24 against only 6% in its previous study between January 9 and February 8. These young voters likely come from Hollande more than any other candidate (perhaps Bayrou), but some might also be drawn from previous apathetic voters who were motivated by Mélenchon’s campaign.

Ifop offers us a very detailed analysis of his electorate by socio-professional category. There are certainly some cases of small samples, but the results are quite interesting. In table form, translated into English, it gives:

| Socio-professional category | % Mélenchon, Ifop Mar 13-27 (avg. 13%) | vs. Ifop Jan 9-Feb 3 |

| Artisans, merchants, farmers and business owners | 10% | +5 |

| Liberal professions (some doctors, lawyers etc) | 11% | +6 |

| Cadres (middle management) of businesses (engineers, admin, commercial, financial analysis etc) | 9% | +4 |

| Cadres (middle management) of the public sector (middle-level public servants, some doctors, professors, school administration, artists, librarians) | 17% | +9 |

| White collar professionals (professions intermédiaires) of the public sector (public servants, teachers, social workers, healthcare sector) | 19% | +5 |

| White collar professionals (professions intermédiaires) of businesses (representatives, salesmen, supervisor, technicians) | 15% | +4 |

| Public sector employees and police/military | 12% | +5 |

| Business employees (private sector workers, employees, secretaries) and commerce employees (cashiers, sellers) | 12% | +5 |

| Direct services to individuals (concierge, hairdresser, childcare, housewives etc) | 8% | +1 |

| Qualified workers | 15% | +6 |

| Non-qualified workers | 20% | +10 |

Mélenchon is catching a very diverse electorate, performing best in the most left-leaning categories and not doing as well in the most right-leaning categories. The core of Mélenchon’s base is made up of public servants, especially those which form a sort of weird left-leaning petite bourgeoisie (though that is not the correct word, you get the point). He appeals to a middle-class electorate, which is concerned about things such as unemployment, cost of living, salaries, poverty and public services. As you can see in the above table, he performs very strongly with professionals and middle-level managerial types in the public sector, a category which includes teachers, social workers, healthcare workers, professors, healthcare and education professionals, school administrators, employees in state enterprises or similar professions. This was Mélenchon’s base before his surge, which gave him a strong footing with ouvriers – especially non-qualified workers. Mélenchon is not recreating the PCF’s old proletarian electorate entirely, but he is doing so in part. Hammering on the leftist rhetoric likely gained him some support or sympathy with unionized workers, who are concerned about losing their jobs or the cost of living or salaries.

Still, Mélenchon’s electorate is much more white-collar than the old PCF’s electorate in the 1970s and 1980s would have been. It is hard to quantify, but he might be attracting some support from particularly left-leaning bobos who are public employees. This is not a particularly ‘revolutionary’ electorate or a ‘protest vote’ electorate, but some might feel Hollande is too soft or too centrist. Furthermore, the collapse of Eva Joly’s candidacy might be attracting some “red greens” to his tent.

Ifop’s study also looked at what were the top policy priorities for Mélenchon’s electorate, compared to the French electorate as a whole. Clearly, Mélenchon’s voters are far more concerned than the average voter about salaries/cost of living (76% vs 54%), poverty (68% vs 52%) and saving public services (52% vs 32%). They are also concerned about matters such as education, healthcare, unemployment or the environment. But compared to the average voter, they are not really concerned as much by the reduction of the public debt (Sarkozy’s voters tend to rank this as one of their top priorities), insecurity/criminality (27% vs 43%) or illegal immigration (12% vs 36%). Marine Le Pen’s voters are disproportionately concerned by such issues, but for Mélenchon’s voters, the top priority are largely middle-class public sector preoccupations (very ‘social’ in nature, rather than ‘moral’ or ‘law and order’). Of course, some of Marine Le Pen’s voters are concerned by ‘social’ issues like these, but her electorate is by far one which is concerned by issues such as immigration or criminality.

5. Nicolas Sarkozy’s gains and a potential runoff victory

The gains made by Nicolas Sarkozy since he announced his candidacy is the second most notable story of this campaign thus far. Once performing extremely weakly in the first round, with only 22-24% support, he has now increased his support to a stronger 27-30% range. He is polling below his first round result in 2007 (31%) which had been a very good result, but he has certainly made up lots of ground. Even in the runoff, where he still trails by a large margin, he has cut Hollande’s lead pretty significantly. From a fairly crazy 20 point gap (60-40), he now trails by a smaller (though still fairly big) margin of 6-10 points.

The graph shows it clearly: Sarkozy’s gains have come at Marine’s expense. Marine Le Pen polled between 16-20%, which could have won her a result higher than her father’s historic 2002 showing (16.9%). She is now down to 13-16%, which would still be a very pleasing result for the FN after the 2007 routs, but underwhelming considering their successes in 2011. Worst, Marine Le Pen is now left fighting Mélenchon for third place.

Nicolas Sarkozy kicked off his campaign on a very right-wing note by placing emphasis on issues such as immigration, security, law and order. In this way, he plays upon the concerns and preoccupations of FN voters. His entourage has made it very clear that Sarkozy’s strategy for underdog reelection is faire campagne “au peuple”, which roughly means a very populist campaign oriented towards the lower middle-classes and working-class.

Sarkozy’s gains with traditionally left-wing or frontiste workers had been, in 2007, one of his main advantages. In 2007, he had already played a similar game with the rhetoric about work, effort, merit and so forth which appealed to FN voters and some working-class voters. However, during his presidency, he lost significant support with this same electorate which became very much anti-Sarkozy by cause of his image (too close to rich people and money), corruption and economic troubles. He is clearly aiming to reconquer the sympathies and vote of those who had voted for him in 2007 (working-class voters, old FN voters) but who had abandoned him in droves beginning in 2009-2010.

Thus far, he has had some success. His standing with ‘CSP-‘ voters (lower socio-professional status) has improved rather significantly since 2011, and while it is still not good enough to win, it gives him reason to hope. With FN voters, he clearly has had some success in ‘poaching’ votes from Marine Le Pen. She peaked too early, banking on the fickle support of unhappy right-wing voters who have jumped back to Sarkozy’s vessels, either convinced by his rhetoric, his new image (for the seven hundredth time) or sympathy for a president who isn’t perfect but who “has done a good job”. Because she peaked too early, she now faces a decline in support as voters look twice on her, especially on her weak points (experience, economic/fiscal policy, foreign policy).

Nicolas Sarkozy banks on three first round results to give him a boost ahead of the runoff: clearly outpolling Hollande, winning over 30% and perhaps winning more than he won in 2007 (31%). It would give him a media narrative as a “comeback kid” who has overperformed expectations (historically, ‘first round boosts’ in runoffs are given to those who have overperformed expectations – such as Jospin in 1995) and who has patched his 2007 electorate back together.

Secondly, to win in the runoff, Sarkozy needs to perform very well with those who voted for Marine Le Pen in the first round. He needs at least two-thirds of their votes, whereas he now wins at most a bit over half of their votes. The problem is that, as Sarkozy eats up her electorate, her base becomes, like her father’s 2007 base, much more working-class/protest voting than otherwise. As in 2007, Sarkozy’s gains with the FN this year have likely proven strongest with the FN’s old base with exurban voters, the petite bourgeoisie and CSP+ (higher socio-professional status). In contrast, she hangs on to a CSP-/working-class electorate which is far more reticent towards Sarkozy and could prefer to vote for Hollande or not vote at all in the runoff.

Ifop had an interesting article which included some observations on vote transfers from Marine’s electorate. Unsurprisingly, those Marine voters who were most likely to go for Sarkozy in the runoff were CSP+ voters, while Marine’s ouvriers were far more resistant of Sarkozy, leaning in large part towards not voting at all or going for Hollande.

Beyond that, Sarkozy also needs to reconquer votes on the centre-right if he is to win in the runoff. This likely means outpolling Hollande by a comfortable margin with Bayrou’s first round supporters. Bayrou’s campaign has been a flop, following a successful entrance in December, where he took some centrist votes from Hollande (former Borloo votes?) and Sarkozy. He has been squished out of a polarized left-right fight, hurt by his lack of charisma and the boredom he generally inspires. He has lost some anti-Sarkozyst moderates to Hollande, but has also failed to cash in from any potential dissatisfaction with UMP moderates from Sarkozy’s right-wing populist campaign. He is probably keeping a more centre-right-UDF style electorate at this point, having lost those left-wing, bobo and anti-system votes he had won in 2007.

Sarkozy has not concerned himself all that much with his problems with moderate and centre-right voters, who have proven, in the past at least, to be clearly unhappy with Sarkozy and the UMP’s right-wing rhetoric and focus on controversial issues such as immigration or criminality. In his present state, it is imperative that Sarkozy regains the support of at least some of these voters, some of whom are attracted to Hollande’s image as a calm, reasonable and fairly pragmatic candidate. Sarkozy should play on his strengths – and Hollande’s weaknesses – that is, his “presidential image” as the best possible leader to deal with the economic crisis and the debt/deficit. In this way, he could appeal more to centre-right voters… but he must resist any urge to go “too far” on the debt reduction theme as to prevent any losses on his right with populist voters hesitating between Marine, him and abstention.

Nicolas Sarkozy remains in a very tough spot for the runoff. In polls, he seems to have “peaked” in the runoff thus far. He has not polled any better than 47%, and consistently polls in a small 45-46% window. This would represent a fairly decisive defeat, a margin which would, if played out on May 6, be much larger than Giscard’s 1981 margin of defeat against Mitterrand. There is, especially on the left, a very strong anti-Sarkozyst element which will be very difficult for him to break.

2012 will most likely resemble 1981 out of any presidential election, rather than the incumbent reelections of 1988 and 2002. In 1988, an incumbent president was reelected because he benefited from a cohabitation which turned him into the “opponent” to an unpopular “incumbent” Prime Minister. Mitterrand no longer took the blame for unpopular government policy, because he was no longer the government. In contrast, he could brand Chirac as a sectarian, divisive right-winger, appearing as a ‘uniter’ against ‘the divider’. In 2002, we all know why Chirac was reelected, but even then, he semi-successfully played on his non-incumbent image to underline the left’s weakness with voters on issues such as immigration and security which played to Le Pen’s strengths and to Jospin’s weaknesses. In 1981, by contrast, an incumbent president was really the incumbent (like Sarkozy), bore the brunt of unpopular policies (Sarkozy perhaps even more so, because of his centralist style) and faced trouble within his own majority (Sarkozy’s problems with his right and ‘left’). On the left, a candidate who had some rivals on his left (Marchais > Mélenchon?) but who could nonetheless play a somewhat left-wing but still fairly moderate campaign which appealed to more centrist, moderate middle-class voters (like Hollande) who were hurt by the economic crisis or unhappy with the incumbent.

…

I do not plan on making any more detailed posts on the election on this blog until the first round. However, I might write a fairly detailed ‘preview’ of the first round for my other blog, World Elections.

Posted on April 11, 2012, in Centre (MoDem etc), Electoral analysis, Far-Left (LO, NPA etc), Far-Right (FN etc), Fifth Republic (1958-), Left (PS, PRG, PCF, Greens, DVG etc), Right (UMP, RPR, UDF, DL, MPF, DVD etc). Bookmark the permalink. 4 Comments.

Great !

Happy to see that we mostly agree.

And to see that you take the time to analyze and publish IFOP and IPSOS detailed data, which I didn’t do 😛

Pingback: Derniers sondages IFOP, BVA et LH2: les sondeurs reviennent à leurs biais, mais les dynamiques Sarkozy et Mélenchon semblent stoppées et Hollande gagne au centre « Sondages 2012 pour l'élection présidentielle en France

Pingback: Election Preview: France 2012 Q&A « World Elections

Pingback: France 2012 « World Elections